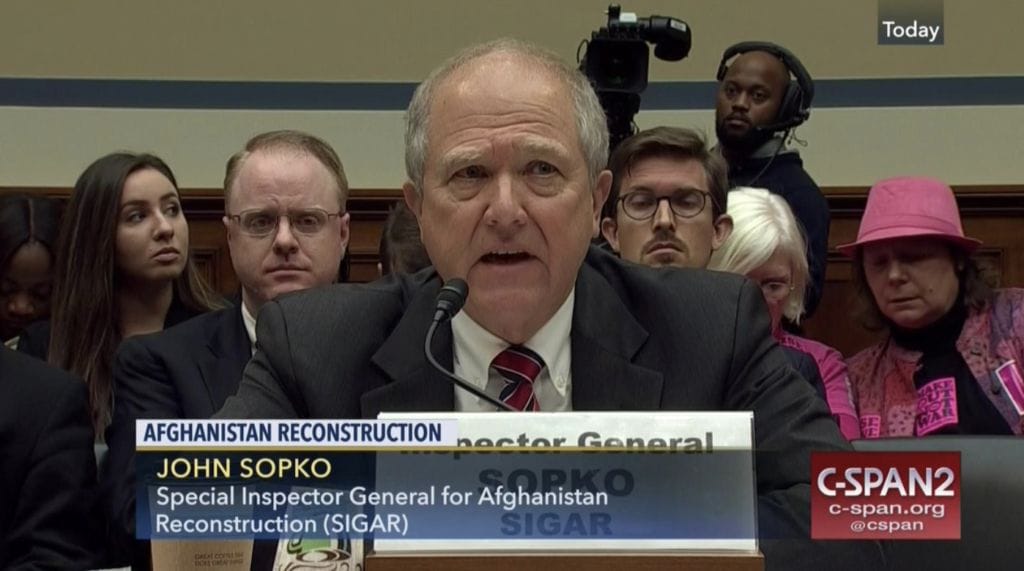

The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), John Sopko has released his interim report analyzing what went wrong in August of 2021 when the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) collapsed.

The interim report, entitled Collapse of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: An Assessment of the Factors That Led to Its Demise is the first U.S. government report to address what happened to the Afghan forces during the botched US withdrawal.

The report was formulated based in part on SIGAR interviews with U.S. and Afghan former government officials and military leaders.

A final version of the report will be released in the Fall of 2022.

Read full report at this link: Collapse of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: An Assessment of the Factors That Led to Its Demise.

Key findings listed below:

- SIGAR found that the single most important factor in the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces’ (ANDSF) collapse in August 2021 was the decision by two U.S. presidents to withdraw U.S. military and contractors from Afghanistan, while Afghan forces remained unable to sustain themselves. (Page 6)

- One former U.S. commander in Afghanistan told SIGAR, “We built that army to run on contractor support. Without it, it can’t function. Game over…when the contractors pulled out, it was like we pulled all the sticks out of the Jenga pile and expected it to stay up.” (Page 13)

- Former Afghan generals told SIGAR that the majority of the U.S.-made UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters were grounded shortly after U.S. contractors withdrew in the spring of 2021 [including those who performed maintenance on those helicopters]. “In a matter of months, 60 percent of the Black Hawks were grounded, with no Afghan or U.S. government plan to bring them back to life,” one Afghan general told SIGAR. As a result, Afghan soldiers in isolated bases were running out of ammunition or dying for lack of medical evacuation capabilities. (Page 14)

- According to an senior Afghan official, it was not until President Biden’s April 14, 2021, announcement of the final troop and contractor withdrawal date that…President Ghani’s inner circle said they realized that the ANDSF had no supply and logistics capability. Although the Afghan government had operated in this way for nearly 20 years, their realization came only 4 months before its collapse. (Page 18)

- The U.S.-Taliban agreement and subsequent withdrawal announcement degraded ANDSF morale. According to ANDSF officials, the U.S.-Taliban agreement was a catalyst for the collapse. A former Afghan commander told SIGAR that the agreement’s psychological impact was so great that the average Afghan soldier switched to survival mode and became susceptible to accepting other offers and deals. Another senior ANDSF official told us that after the Doha agreement was signed, Afghan soldiers knew they were not the winner. (Page 6)

- After the signing of the U.S.-Taliban agreement, the U.S. military changed its level of military support to the ANDSF overnight, leaving the ANDSF without a critically important force multiplier: U.S. airstrikes. In 2019, the United States conducted 7,423 airstrikes, the most since at least 2009. In 2020, the U.S. conducted only 1,631 airstrikes, with almost half occurring in the two months prior to the U.S.-Taliban agreement. A former commander of Afghanistan’s Joint Special Operations Command told SIGAR that “overnight…98 percent of U.S. airstrikes had ceased.” (Page 10-11)

- Many factors affected the ANDSF’s determination to keep fighting: low salaries; poor logistics that led to food, water, and ammunition shortages; and corrupt commanders who colluded with contractors to skim off food and fuel contracts. But the root cause of the morale crisis may have been the lack of ANDSF buy-in with the Afghan central government.(Page 9)

- One former Afghan government official told SIGAR that following the U.S.-Taliban agreement, President Ghani began to suspect that the United States wanted to remove him from power. That official and a former Afghan general believed Ghani feared a military coup. According to the general, Ghani became a “paranoid president…afraid of his own countrymen” and of U.S.-trained Afghan officers. (Page 17)

- According to a former Afghan general, in the week before Kabul fell, President Ghani replaced the new generation of young U.S.-trained Afghan officers with an old guard of Communist generals in almost all of the army corps. Ghani, that general said, was “changing commanders constantly [to] bring back some of the old-school Communist generals who [he] saw as loyal to him, instead of these American-trained young officers who he [mostly] feared.” (Page 17)

- According to a former Afghan Interior Minister, Afghan security officials briefed President Ghani about the impending U.S. withdrawal – five days before the April 14 announcement – but Afghanistan’s then-vice president told President Ghani that this was a U.S. plot, and the briefing was ignored. (Page 18)

- The U.S.-Taliban agreement introduced tremendous uncertainty into the U.S.-Afghan relationship. Many of its provisions were not public, but are believed to be contained in secret written and verbal agreements between U.S. and Taliban envoys. Some U.S. analysts believe that one classified annex detailed the Taliban’s counterterrorism commitments, while a second classified annex detailed U.S. and Taliban restrictions on fighting. SIGAR was not able to obtain copies of these annexes, despite official requests made to the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of State. (Page 11)

- Afghan officials, largely removed from the negotiations, struggled most of all to understand what the United States had agreed to with the Taliban. According to Afghan government officials, the U.S. military never clearly communicated the specifics of its policy changes to the Ghani administration or ANDSF leadership. The Taliban’s operations and tactics, however, suggested that they may have had a better understanding of new U.S. levels of support the United States was willing to provide to the ANDSF following the signing of the U.S.-Taliban agreement. (Page 11)

- According to a former Afghan general, in a broad sense, the U.S. military took on the role of a referee and watched the Afghan government and Taliban fight, something the general referred to as “a sick game.” According to that general, Afghan troops had not only lost U.S. support for offensive operations, they no longer knew if or when U.S. forces would come to their defense. U.S. inaction fueled mistrust among the ANDSF toward the United States and their own government. (Page 12)

- Under the U.S.-Taliban agreement’s rules, U.S. aircraft could not target the Taliban groups that were waiting more than 500 meters away—the groups “beyond the contact” that would engage in the second, third, or fourth wave to defeat the last ANDSF units. A senior Afghan official said this was a loophole that the Taliban used in their targeting to their advantage. (Page 12)

- While ANDSF forces were limited to a defensive posture, the Taliban took advantage of its freedom of movement to launch an undeclared offensive targeting vulnerable ANDSF supply lines. According to an Afghan general, an Afghan military assessment found that in 2020 the Taliban caused $600 million in damages to roads, electricity lines, schools, canals, and bridges in Helmand Province alone. “It was the same story all across the country,” the general told SIGAR. (Page 20)

- The secrecy around U.S.-Taliban negotiations and the Doha agreement meant there was a lack of official information for the ANDSF. Taliban propaganda weaponized that vacuum against local commanders and elders by claiming the Taliban had a secret deal with the United States for certain districts or provinces to be surrendered to them. One former senior Afghan official told SIGAR that the Taliban used this tactic quite effectively, telling forces, “They’re going to give us this territory, why would you want to fight? We will forgive you…we will even give you 5,000 Afghanis for your travel expenses.” Having not been paid for months, the police would abandon their posts. Then, “the army panicked; they thought the police made a deal, and they’re going to be butchered. So, the army made a run for it too. That started a cascading effect.” (Page 23)

- SIGAR found that no one country or agency had ownership of the ANDSF development mission. Instead, ownership existed within a NATO-led coalition and with temporary organizations. All of these entities were staffed with a constantly changing rotation of military and civilian advisors. The constant personnel turnover impeded continuity and institutional memory. The result was an uncoordinated approach that plagued the entire mission. (See “What SIGAR Found”: Page ii (2nd Page))

- SIGAR found that during the 2009 to 2014 military surge years, the U.S. military struggled to balance the competing goals of improving security to allow for a U.S. drawdown with developing self-sustaining ANDSF capabilities. (Page 24)

- The Afghan government failed to develop a workable national security strategy that could assume responsibility for nationwide security following the withdrawal of U.S. forces. One of the main problems was the lack of nationally oriented leaders that were competent in managing and coordinating national security affairs. (Page 17)

- According to a senior State Department official, U.S. government officials, including members of Congress with whom President Ghani communicated through unofficial channels, reinforced President Ghani’s misperceptions about the U.S. withdrawal. The apparent disconnect between unofficial channels of support and public pronouncements gave President Ghani the impression that the U.S. government was not altogether on the same page on full withdrawal, and that the withdrawal announcement was intended to shape his behavior, as opposed to being official U.S. policy. (Page 12-13)

- SIGAR found nine factors that contributed to U.S. and Afghan governments’ ineffectiveness and inefficiencies in reconstructing Afghanistan’s entire security sector over the 20-year mission. (See list of factors, Page 24)

- The length of the U.S. commitment was disconnected from a realistic understanding of the time required to build a self-sustaining security sector—a process that took decades to achieve in South Korea. Constantly changing and politically driven milestones for U.S. engagement undermined the its ability to set realistic goals for building a capable and self-sustaining military and police force. Further, many of the up-and-coming ANDSF generals had only a decade of experience; most general officers in the U.S. military have twice as much. Adapting a decades-long process to an unrealistically short timeline was reminiscent of the U.S. experiences in Vietnam.(Page ii; see Appendix II for more details)

Conclusion: The U.S. approach to reconstructing the ANDSF lacked the political will to dedicate the time and resources necessary to reconstruct an entire security sector in a war-torn and impoverished country. As a result, the U.S. created an ANDSF that could not operate independently, milestones for ANDSF capability development were unrealistic, and the eventual collapse of the ANDSF’s was predictable. After 20 years of training and development, the ANDSF never became a cohesive, substantive force capable of operating on its own.

The U.S. and Afghan governments share in the blame. Neither side appeared to have the political commitment to doing what it would take to address the challenges, including devoting the time and resources necessary to develop a professional ANDSF, a multi-generational process.

In essence, U.S. and Afghan efforts to cultivate an effective and sustainable security assistance sector were likely to fail from the beginning. The February 2020 decision to commit to a rapid U.S. military withdrawal sealed the ANDSF’s fate. (See full CONCLUSION, Page 38)

NO MATTER HOW IT IS SUGAR COATED:IT ALL FALLS ON BIDEN AND THE DNC. THEY HAVE A LOT OF BLOOD ON THERE HANDS FOR THIS ACT

So who was president of the US when it was signed in Doha, Qatar February 29, 2020? Not a Biden fan, but there were plenty of blunders to go around.

This is why don’t fight wars for 20 years. We should have been out of Afghanistan no later then 2004. Not to mention, never should’ve went into Iraq. This whole thing can be pinned on one administration, IMO. Bush/Cheney.